The Banned Grapes of Wine History.

In a world where wine is both a pleasure and a regulated agricultural product, the grapes that fill your glass are not always a matter of tradition, terroir, or taste—but of law. The wines you sip, cellar, or celebrate with are shaped not only by centuries of viticultural evolution but also by sweeping legislation that determines what may—and may not—be grown, labeled, and sold as wine.

Among the many curiosities of global wine law lies a particularly juicy topic: forbidden fruit—grape varieties that have been banned or heavily restricted, particularly in the European Union. Their names whisper through the back alleys of viticultural history like outlawed poets: Noah, Othello, Isabelle, Jacquez, Clinton, and Herbemont.

These grapes, many of them American in origin or hybridized with American species, were once planted across Europe, often out of necessity. Today, they are outlawed under Article 81 of EU Regulation 1308/2013, which governs the production and classification of wine grape varieties in the Union. The regulation states:

“Only wine grape varieties meeting the following conditions may be classified by Member States:

(a) the variety concerned belongs to the species Vitis vinifera or comes from a cross between the species Vitis vinifera and other species of the genus Vitis;

(b) the variety is not one of the following: Noah, Othello, Isabelle, Jacquez, Clinton, and Herbemont.”

Let’s explore the forbidden fruit of wine—the banned grapes themselves, their unique characteristics, why they were planted in the first place, and what caused their ultimate prohibition. These are not just curiosities; they are the ghosts of a viticultural rebellion, and their legacy still haunts the fringes of wine culture today.

The Historical Context

In the late 19th century, Vitis vinifera vineyards across Europe were devastated by the Phylloxera epidemic, a microscopic root-feeding insect inadvertently introduced from North America. With no resistance to this louse, Europe’s noble vines died en masse. Desperation led vintners to seek salvation in the very continent that brought the plague—North America.

American grape varieties like Vitis labrusca, Vitis riparia, and their hybrids offered something miraculous: phylloxera resistance. Initially, some of these American vines were planted directly in European soil to replace dead vines and maintain wine production. Many grew vigorously and bore fruit prolifically. But their success was short-lived.

Six Forbidden Grape Varieties

Noah

Origin: A hybrid of Vitis riparia × Vitis labrusca

Flavors: Pungent, foxy (a musky, earthy flavor common in V. labrusca), often described as wild strawberry or candied grape

Why It Was Banned:

- Intense foxy aroma and taste considered undesirable and un-winelike

- Thin-skinned berries prone to rot in certain climates

- Associated with poor-quality table wines in post-Phylloxera France

Othello

Origin: Vitis labrusca hybrid, possibly including Vitis vinifera genetics

Flavors: Deeply pigmented with earthy, gamey notes and labrusca musk

Why It Was Banned:

- As with other hybrids, its sensory profile did not meet European expectations for fine wine

- Resistance to European fermentation techniques (longer ferment times, unpredictable aromatics)

- Accused of contributing to public intoxication due to strong, rustic flavors that masked alcohol strength

Isabelle

Origin: Vitis labrusca × Vitis vinifera

Flavors: Strawberry, bubblegum, purple grape juice

Why It Was Banned:

- High methanol content feared to be harmful in large doses (though this has been contested)

- Overpowering aromas viewed as unrefined by French authorities

- Once widespread in Italy and Southern France, it became a symbol of cheap, rural wine

Jacquez (a.k.a. Black Spanish)

Origin: Possibly a cross of Vitis aestivalis, V. vinifera, and V. cinerea

Flavors: Dark berry, spicy, tannic, with notes of underbrush

Why It Was Banned:

- Despite some early promise, it was considered too unconventional

- Part of the hybrid scare that followed Isabelle and Noah

- Viewed as incompatible with traditional European wine culture

Clinton

Origin: Vitis riparia × Vitis labrusca

Flavors: Herbaceous, sour cherry, strong wild grape flavor

Why It Was Banned:

- Extreme foxy aroma off-putting to most European palates

- Used primarily in rural, peasant wines during the Phylloxera crisis

- Perceived as lacking refinement and fermentation stability

Herbemont

Origin: Possibly a hybrid of Vitis vinifera and Vitis aestivalis

Flavors: Musky, perfumed, and surprisingly delicate in some climates

Why It Was Banned:

- Less widespread than the others, but lumped into the ban due to hybrid ancestry

- Suspected methanol risks and lack of predictable vinification

- Part of a general effort to restore vinifera-only wine law supremacy

The Real Reasons Behind the Ban

While flavor and fermentation challenges were the most visible justifications for banning these grapes, the real reasons go deeper. These include:

Cultural Superiority and Market Protection

Post-Phylloxera, France in particular wanted to reclaim wine as a refined agricultural product, not a rural necessity. American and hybrid grapes represented chaos—a collapse of tradition. By the 20th century, wine laws began to frame hybrids as a threat to the AOC system and the image of French wine.

Fear of Methanol Toxicity

Some hybrids, particularly labrusca crosses, were accused of producing higher levels of methanol during fermentation. However, modern science suggests the levels were likely within safe margins if fermented correctly. Still, the fear took root—and the narrative stuck.

Economic Centralization

France and later the EU wanted to consolidate the wine industry around traditional grapes, often to protect exports and standardize quality. Hybrids were associated with rustic, small-scale producers. The bans effectively curtailed these competitors.

Sensory Profiling

The term “foxy,” used to describe labrusca hybrids, became shorthand for unacceptable. The bias was less scientific than aesthetic—a rejection of New World taste in favor of the European palate.

Are These Grapes Really Dangerous or Just Different?

In recent years, many winemakers, particularly natural wine producers and sustainable agriculture advocates, have questioned these bans. Some point to:

- The resilience of these grapes in the face of climate change

- Their low-input agricultural potential (less need for pesticides)

- The possibility of redefining wine taste beyond the rigid expectations of 20th-century Europe

Regions in the U.S., Canada, and even some rebel producers in France and Italy have continued to experiment—often quietly—with these grapes.

The Future of Forbidden Fruit

As the wine world grapples with climate change, disease pressure, and evolving consumer taste, the question lingers:

Should the laws of the past dictate the palate of the future?

Already, new EU regulations have begun allowing more hybrid crossings for certain uses (especially sparkling and low-alcohol wines), and experimental vineyards are pushing boundaries. The forbidden fruit, once cast out of Eden, is being quietly replanted.

One notable example comes from the Azores, where winemaker António Maçanita embraces the outlawed Isabella grape in a wine named “Isabella a Proibida”. The grape, banned under EU wine laws for use in classified quality wines (PDO/PGI), is grown on ancient pergola-trained vines on the island of Pico.

This wine pays tribute to the past, celebrating the resilience of a grape long maligned by regulators but still cherished by local growers. Such wines are challenging assumptions and redefining what quality, character, and authenticity mean in a changing world.

Here’s a quick reference visual that outlines the main Vitis species used in wine production (or breeding).

Vitis Species and Associated Grape Varietals

| Vitis Species | Common Traits | Example Varietals |

|---|---|---|

| Vitis vinifera | European origin; preferred for fine wine; low disease resistance | Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Riesling, Tempranillo, Nebbiolo |

| Vitis labrusca | Native to eastern North America; “foxy” aroma; cold-hardy | Concord, Niagara, Isabella, Catawba |

| Vitis riparia | Extremely cold-hardy; used in rootstocks and hybrids | Used for breeding: Marechal Foch, Frontenac |

| Vitis aestivalis | High disease resistance; poor graft compatibility; non-foxy | Norton (Cynthiana), Herbemont |

| Vitis berlandieri | High lime tolerance; used mainly in rootstocks | Rootstock parent: 41B, 5BB |

| Vitis rupestris | Deep root system; phylloxera resistant; drought-tolerant | Rootstock parent: St. George, 110R |

| Vitis amurensis | Native to East Asia; extremely cold-hardy; growing in popularity in China & Russia | Rondo (hybrid), Koshu (disputed origins) |

| Interspecific Hybrids | Combines vinifera and American species; disease-resistant; sometimes banned | Baco Noir, Chambourcin, Seyval Blanc, Jacquez |

A Toast to the Outcasts

The next time you sip a glass of classic Bordeaux or Burgundy, spare a thought for the outlawed grapes that helped keep wine alive during one of its darkest hours. They may not be in your glass—but they are in your history.

And if you’re ever offered a bottle of forbidden wine, made in defiance of convention and law, don’t refuse it. Raise a glass and taste the rebellion. Cheers 🍷

Further Reading & Tasting Tips

- Seek out Black Spanish (Jacquez) wines from Texas or Mexico.

- Try a hybrid wine from Canada or Vermont (Frontenac, Marquette, or Baco Noir).

- Look for limited-edition natural wines using heritage hybrids in France’s Loire Valley or Italy’s north.

- Read “The Botanist and the Vintner” by Christy Campbell for Phylloxera-era drama.

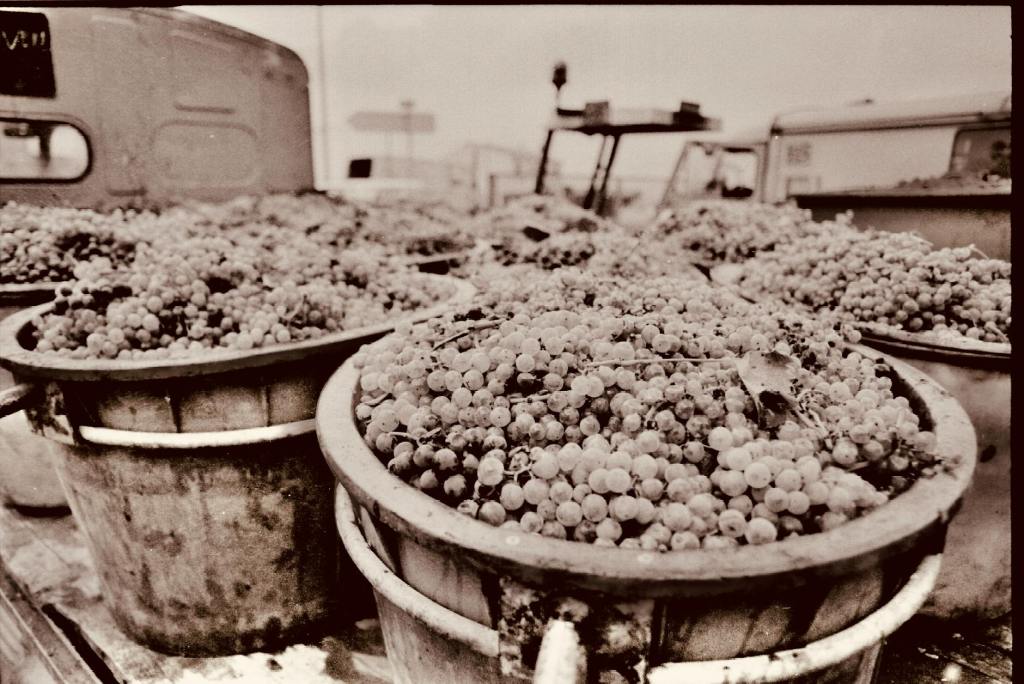

Cover Photo by Emmanuel Codden on Pexels.com

We welcome feedback…