Let’s face it—sugar gets a bad rap these days. Whether it’s hiding in your cereal, lurking in sauces, or being dissected on nutrition labels, sugar has become a buzzword. But in the world of wine, sugar isn’t some evil saboteur. It’s the lifeblood of fermentation, the foundation of balance, and sometimes—just sometimes—the reason your wine sings with ripe peach or sassy cherry notes.

Yet, sugar in wine is wildly misunderstood. Just because a wine tastes sweet doesn’t necessarily mean it’s sugary. And just because a wine is dry doesn’t mean sugar isn’t playing its part in the background. So let’s peel back the grape skin and dive into the sticky truth about sugar in wine.

The Sugars in Wine Grapes

Grapes are little chemistry labs on a vine, and their sugars are anything but simple. Here are the main players:

- Glucose – A common simple sugar, and yeast’s favorite snack. Present in nearly equal amounts with fructose during grape ripening.

- Fructose – The fruitier twin of glucose. It’s sweeter to taste and becomes dominant as grapes ripen and overripen.

- Sucrose – Rare in grapes. It’s broken down into glucose and fructose almost immediately.

- Galactose & Sorbitol – Present in tiny amounts and not very influential in fermentation, but still part of the biochemical crew.

Fun fact: Only glucose and fructose are fermentable sugars. The others? They’re just hanging out in the background like flavor groupies.

Sugar’s Purpose in Wine

Let’s get one thing straight: Residual Sugar (RS) is not the same as perceived sweetness.

RS is the sugar left behind after fermentation. This can be intentional (hello, Riesling!) or accidental (hi, stuck fermentation). But sweetness on the palate? That’s a combination of sugar, acidity, alcohol, tannin, and fruitiness. A dry wine can taste sweet if it’s loaded with ripe fruit and low in acid.

Sugar’s role in winemaking is multifaceted:

- It feeds the yeast, which convert sugar into alcohol, CO₂, and flavor compounds.

- It influences mouthfeel and body—sweeter wines often feel fuller.

- It helps balance acidity, especially in cool-climate wines.

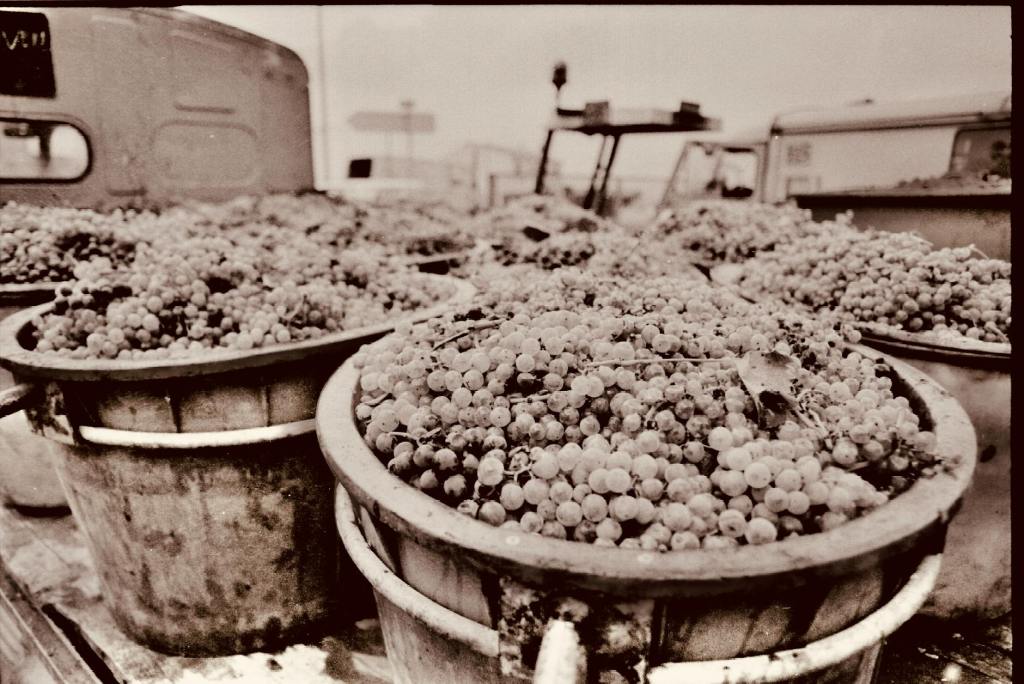

From Veraison to Harvest

At the start of grape development, acids dominate. Think green, tart, mouth-puckering grapes. But as the grape matures (a process called veraison), chlorophyll fades and sugar floods in.

Initially, glucose and fructose arrive in balance (1:1). But as ripening continues:

- Fructose levels rise faster.

- Glucose levels plateau or even decline slightly.

By harvest, fructose becomes the dominant sugar, and that’s key—because fructose is about 1.5x sweeter than glucose. So a late-harvest wine? It’s richer in fructose, which contributes more to sweetness—especially if the wine is made to retain RS.

Why Some Wines Are Sweeter Than Others

The reasons are delightfully diverse:

- Yeast Selection & Fermentation Control

Some winemakers stop fermentation early—either by chilling the wine, adding sulfur, or filtering out the yeast—leaving unfermented sugar behind. - Grape Ripeness

Late harvest, botrytized (noble rot), and dried grapes (passito method) have sky-high sugar levels. Not all of it gets fermented, especially in high-alcohol environments. - Fortification

In wines like Port, fermentation is halted by adding brandy, locking in sugars and boosting alcohol. - Winemaking Traditions

German Kabinett vs. Auslese Riesling, Vouvray Sec vs. Moelleux—some regions embrace sugar as a stylistic hallmark. - Intentional Back-Sweetening

Yes, in some cases, especially in inexpensive wines or mass-market blends, sugar is added after fermentation to soften rough edges or mask imbalances. (We see you, off-dry Moscato.)

A Lighthearted Guide to Residual Sugar

| Style | RS Range (g/L) | Common Wines | Taste Perception |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Dry | 0–1 | Brut Champagne, Muscadet | Sharp, crisp, dry AF |

| Dry | 1–10 | Sancerre, Chablis, Chianti | Dry, but fruity is OK |

| Off-Dry | 10–30 | Riesling Kabinett, Vouvray | Light sweetness |

| Medium Sweet | 30–60 | Moscato, Gewürztraminer | Noticeable but refreshing |

| Sweet | 60–120 | Port, Sauternes | Dessert-level richness |

| Lusciously Sweet | 120+ | Ice Wine, Tokaji Aszú 6 Puttonyos | Nectar of the gods |

Dessert, or Just a Sweet Moment?

Here’s the big takeaway: Sweetness in wine isn’t always about sugar.

That plush California Chardonnay that reminds you of a tropical smoothie? It might have almost no residual sugar but loads of ripe fruit and new oak.

That Italian Brachetto you had on a patio last summer? Light in alcohol, fizzing with red berry notes, and low-key sugar? Yeah, that was actually sweet.

Respect the Sugar

Sugar is the unsung hero of wine. Without it, there’d be no fermentation, no alcohol, no balance. It’s the yeast’s playground, the winemaker’s tool, and the drinker’s delight.

So next time someone scoffs at sweet wines, hand them a glass of well-made Spätlese or Tokaji and watch their misconceptions melt away like sorbet on a summer day.

Because sometimes… life really is sweeter with wine. Cheers 🍷

Bonus Sip: Sweet Surprises & Sugar Truths

Now that we’ve unraveled the mysteries of sugar in wine, it’s time to sweeten the deal. Below you’ll find a curated list of exceptional sweet wines worth exploring, along with a breakdown of common misconceptions that often lead wine lovers astray. Whether you’re a die-hard dry drinker or a sweet wine skeptic, these bonus sips of knowledge might just change the way you see—and taste—wine. Cheers to keeping an open mind and an open palate!

Misconceptions & Misinterpretations

Let’s get this out of the way—sweet wine does not equal cheap wine, and dry wine does not always mean better wine. Somewhere along the way, the wine world developed a bit of snobbery around sugar. The modern palate, shaped by marketing and misunderstood wine rules, has come to associate sweetness with mass-produced, low-quality wines.

That’s simply not true.

Many of the world’s most prestigious wines are sweet—intentionally and artfully so. A bottle of Sauternes from Château d’Yquem can fetch thousands of dollars and age gracefully for decades. German Rieslings labeled Auslese or Trockenbeerenauslese are crafted with painstaking precision. Tokaji Aszú from Hungary was once called the “Wine of Kings, King of Wines” by Louis XIV, and for good reason.

Related SOMM&SOMM Article: Wine Styles: Late Harvest Wines

What’s really happening is that perceived sweetness is being mistaken for residual sugar. A juicy Malbec with ripe plum and chocolate notes might be totally dry (under 2 g/L RS), but your brain reads all that ripe fruit as “sweet.” Meanwhile, a high-acid Riesling with 25 g/L RS might come off as light, zippy, and almost dry due to the acidity balancing the sugar.

So instead of treating sugar like a four-letter word, think of it like salt in food. Used well, it elevates everything.

Best Intentionally Sweet Wines to Try

If you’ve been living in the “dry only” camp, consider this your invitation to the sweet side of the cellar. These aren’t syrupy bottom-shelf bombs. These are masterful wines that showcase the balance between richness, acidity, aromatics, and craftsmanship.

Riesling (Germany, Austria, Alsace)

One of the most versatile and age-worthy white wines on earth. Styles range from off-dry Kabinett to decadently sweet Trockenbeerenauslese (TBA). Look for Mosel Rieslings with high acidity that keep sweetness refreshing, not cloying.

Tokaji Aszú (Hungary)

Made from botrytized Furmint grapes, Tokaji Aszú is honeyed, nutty, and complex. Labeled by “puttonyos,” which refer to the level of sweetness (3 to 6). The 5–6 Puttonyos level is where magic happens.

Sauternes (France – Bordeaux)

A noble rot wine made primarily from Sémillon and Sauvignon Blanc. Think candied citrus, saffron, honey, and apricot. The acidity is key—it balances the intense sweetness beautifully.

Vin Santo (Italy – Tuscany)

A luscious dessert wine made from dried Trebbiano and Malvasia grapes. Notes of caramel, toasted almond, and orange peel make it ideal with biscotti—or just on its own by a fire.

Ice Wine / Eiswein (Germany, Canada)

These grapes are harvested while frozen on the vine, concentrating the sugars and flavors. The result is intensely sweet, with bracing acidity. Canada’s Niagara region and Germany’s Rheinhessen make some of the best.

Recioto della Valpolicella (Italy – Veneto)

Made from partially dried Corvina grapes (the same ones used in Amarone), this red dessert wine is rich, raisiny, and chocolatey—perfect with dark chocolate cake or strong cheese.

Muscat/Moscato d’Asti (Italy – Piedmont)

Low in alcohol, lightly sparkling, and delicately sweet. This one’s your picnic or brunch buddy, best served cold and sipped with fruit tarts or creamy cheeses.

Sweet wines—when done right—are a celebration of craft, patience, and nature. They aren’t just dessert wines; they’re experience wines, meant to be savored slowly, with food or without. So whether you’re a sweet wine skeptic or a seasoned sipper, the world of sugar in wine is worth a second look… and a generous pour.

Now go forth and sweeten your wine wisdom! 🍷✨ Want more deep dives like this? Stay tuned at SOMM&SOMM, where curiosity and corks collide.

You must be logged in to post a comment.