History, Styles, and Pairings Beyond Rice.

Sake is one of those beverages that sparks curiosity the moment it’s poured. Often described as “rice wine,” it sits in a category all its own—neither wine, beer, nor spirit, but a unique fermented drink with an ancient heritage. For sommeliers, wine educators, and enthusiasts alike, sake offers an opportunity to explore tradition, craftsmanship, and unexpected food pairings.

The Origins of Sake

The story of sake begins over 2,000 years ago in Japan. Early rice cultivation techniques—likely borrowed from China—allowed rice to be grown in abundance, and fermentation soon followed.

The earliest forms of sake were very different from what we know today. One of the oldest methods was kuchikami-no-sake, literally “mouth-chewed sake,” in which villagers chewed rice and nuts, then spit the mash into communal vessels. The enzymes in saliva helped convert starches into sugars, and natural yeast performed the fermentation. (Thankfully, brewing techniques evolved.)

By the 8th century, sake had become a central part of Shinto rituals and court ceremonies. Shrines brewed sake as offerings to the gods, and it became a symbol of purity and community. In fact, even today, sake is still deeply tied to spiritual traditions—shared at weddings, festivals, and new year celebrations as a blessing for harmony and prosperity.

The artistry lies in the brewer’s choices: how much rice to polish, what yeast strain to use, whether to pasteurize, and how to balance purity with umami.

The Art of Brewing Sake

Though often called a rice wine, sake production is actually closer to brewing beer, since starch must be converted into sugar before fermentation. The process is meticulous, and every step influences the final flavor:

- Rice polishing (Seimai-buai) – Special sake rice (shuzō-kōtekimai) is milled to remove outer layers of protein and fat, leaving a starchy core. The more the rice is polished, the cleaner and more delicate the flavor.

- Example: Ginjo and Daiginjo styles require at least 40–50% of the rice to be milled away.

- Washing, soaking, steaming – The polished rice is carefully hydrated and steamed, ensuring the right texture for fermentation.

- Koji-making – The soul of sake. A portion of rice is inoculated with Aspergillus oryzae mold, which produces enzymes to break starch into sugar. This process is done in a hot, humid room, with brewers tending the rice around the clock.

Beyond Sake: Aspergillus oryzae and the Magic of Soy Sauce

The same humble mold that transforms rice into the foundation for sake—Aspergillus oryzae—also plays a starring role in one of Japan’s most iconic seasonings: soy sauce. In soy sauce production, A. oryzae is cultivated on a mixture of steamed soybeans and roasted wheat, creating what’s known as koji. The enzymes produced by the mold break down proteins into amino acids and starches into simple sugars.

This enzymatic alchemy is what gives soy sauce its deep savory quality, rich umami, and characteristic complexity. After koji preparation, the mixture ferments slowly in brine for months or even years, developing the layered flavors that make soy sauce a cornerstone of Japanese cuisine—and an indispensable partner to sake at the dinner table.

Just as with sake, the artistry lies in balancing time, fermentation, and microbial activity to coax out flavors both bold and nuanced. The presence of A. oryzae in both beverages and condiments highlights Japan’s centuries-long mastery of fermentation as a way of elevating simple grains and beans into cultural treasures.

- Shubo (starter culture) – Koji rice, water, yeast, and more steamed rice form the fermentation starter, which builds yeast strength and flavor precursors.

- Moromi (main mash) – Over four days, rice, water, and koji are added in stages. This results in a simultaneous saccharification and fermentation—unique to sake.

- Pressing, filtering, pasteurization, aging – Once fermentation is complete, sake is pressed to separate the liquid, filtered, pasteurized, and aged (typically for 6–12 months).

Types of Sake

The classification of sake often comes down to rice polishing and whether alcohol is added. Here are the key categories:

- Junmai – Pure rice sake (no distilled alcohol added). Bold, savory, often higher in umami.

- Honjozo – A touch of distilled alcohol is added to enhance aroma and texture. Lighter and more fragrant.

- Ginjo – Rice polished to at least 60%. Aromatic, elegant, fruit-driven.

- Daiginjo – Rice polished to at least 50%. Luxurious, delicate, highly aromatic.

- Tokubetsu (“special”) – Indicates a special brewing technique or higher-than-required polishing.

- Nigori – Cloudy, unfiltered sake with a creamy texture and hint of sweetness.

- Namazake – Unpasteurized sake. Fresh, lively, must be kept refrigerated.

- Koshu – Aged sake. Amber-hued with oxidative notes like sherry or Madeira.

- Sparkling sake – Carbonated, refreshing, often slightly sweet.

Terminology on a Bottle

When choosing sake, a few key terms help decode what’s inside:

- Seimai-buai – Rice polishing ratio (% of rice remaining after milling).

- Nihonshu-do – Sake meter value (SMV). Indicates sweetness or dryness: negative = sweeter, positive = drier.

- Acidity (San-do) – Higher acidity makes sake crisp and food-friendly.

- Nama – Unpasteurized. Must be chilled.

- Genshu – Undiluted. Higher alcohol, often rich and bold.

Temperature and Glassware

One of the joys of sake is its versatility in temperature:

- Chilled (5–10°C / 40–50°F) – Best for delicate, aromatic styles (Ginjo, Daiginjo, Namazake).

- Room temperature – Junmai and Honjozo shine here, showing full flavor and umami.

- Warm (40–55°C / 104–131°F) – Brings comfort and amplifies savory notes in robust Junmai or Honjozo. Avoid heating aromatic Ginjo/Daiginjo—heat will mute their elegance.

Glassware also plays a role:

- Traditional: small ceramic ochoko cups or wooden masu boxes.

- Modern: wine glasses, which allow aromatic styles to blossom. Sommeliers often recommend using white wine glasses for premium Ginjo/Daiginjo.

Classic Pairings

Sake is famously versatile with food—its low acidity and umami-friendly profile make it shine where wine can struggle.

- Sushi and sashimi (classic)

- Tempura (light, crisp styles)

- Grilled yakitori (umami-rich Junmai)

- Hot pot dishes (nabe)

Surprise Pairings

Sake doesn’t stop at Japanese cuisine. With its balance of umami, sweetness, and subtle acidity, it pairs beautifully with international dishes:

- Cheese – Creamy Brie with Daiginjo, blue cheese with aged Koshu.

- Steak – Rich Junmai or Genshu cuts through the fat as well as Cabernet.

- Spicy Thai or Indian – Nigori or lightly sweet sake balances heat.

- BBQ – Smoky grilled pork or brisket with Honjozo or Koshu.

- Chocolate desserts – Nigori sake works as a sweet complement.

Soju vs. Sake: What’s the Difference?

It’s easy to confuse sake with soju, but they’re distinct:

- Sake – Japanese, brewed, 12–16% ABV, made from rice and water, enjoyed like wine.

- Soju – Korean, distilled, 16–25% ABV (sometimes higher), traditionally made from rice, sweet potato, or barley. Similar to vodka but softer and often lightly sweet.

Think of sake as closer to wine/beer, and soju as a spirit. Both, however, share cultural importance and are designed for communal enjoyment.

Final Pour

Sake is more than an exotic curiosity—it’s a reflection of Japan’s culture, history, and artistry. From the precision of rice polishing to the warmth of shared rituals, sake continues to evolve while staying deeply rooted in tradition.

For sommeliers and enthusiasts alike, sake is an essential part of the conversation when guiding guests through beverage choices. Whether served chilled in a wine glass with sushi, warmed in an ochoko with grilled meats, or poured alongside cheese and chocolate, sake has earned its place on the global table.

Kanpai! 🍶

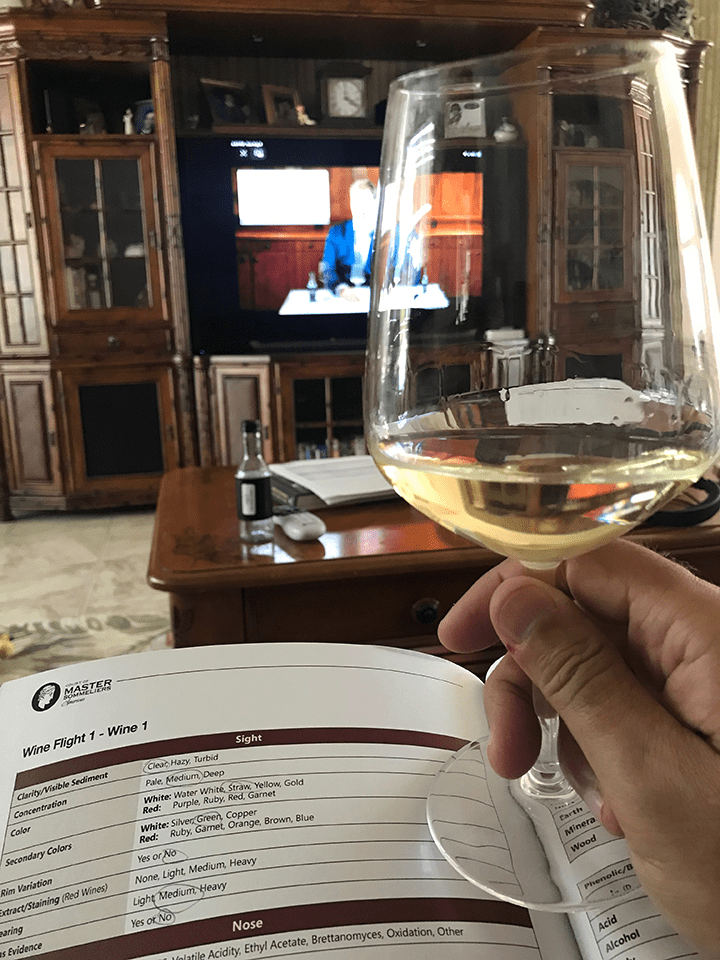

Worth Mentioning: Sake in the Sommelier’s Journey

One of the distinctions in wine education is how different organizations approach beverages beyond wine. The Court of Master Sommeliers (CMS) places strong emphasis on a broad understanding of not only wine, but also beer, spirits, and sake. This reflects the reality of the dining room, where guests often seek diverse options. By contrast, programs such as the WSET or Society of Wine Educators remain more wine-centric, with limited exploration of sake.

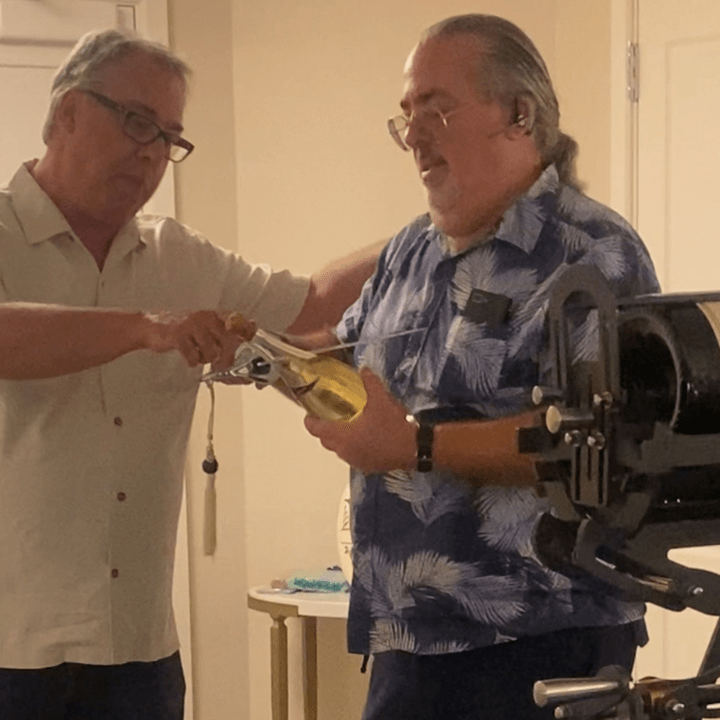

We were fortunate to dive deep into the world of sake during our CMS studies—learning not just its history and classifications, but how to serve, pair, and present it with confidence. That education continues to enrich our work today, allowing us to share sake’s beauty and versatility with guests who might otherwise overlook this extraordinary beverage.

Cover photo by Airam Dato-on on Pexels.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.